The men who want to solve the market: how retail investors can win the zero-sum game

Retail investors are now inclined to take more risks in the esoteric world of derivatives. This behavioural change is the result of a quest for dopamine rush in the age of social media and instant gratification. Will it end well? The answer lies in the ability to overcome paradox of skill.

In 2019, Sandeep Joshi, a well-known dentist in Delhi, caught up with his mentor from medical college days. A few months away from retirement, Joshi’s mentor was in a reflective mood and had a piece of advice for his old student. “Start preparing early for your retired life. It’s important to develop an additional source of income to keep oneself financially and mentally agile,” he said.

Joshi had casually parked that thought in the ‘to-do compartment’ of his mind, until one day it struck him that his interest in investing and trading could be developed into a second career. So, the dentist began his trading journey the old-fashioned way with a copy of John C Hull’s Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives. He also started watching trading videos on YouTube.

Slowly, derivatives trading started growing on him. In 2020, when Covid-19 hit and the world went into a lockdown, Joshi could devote more time to his second profession as a derivatives trader.

Thousands of Joshis were born during the pandemic. And this new breed of market participants is redrawing the contours of Indian equity markets.

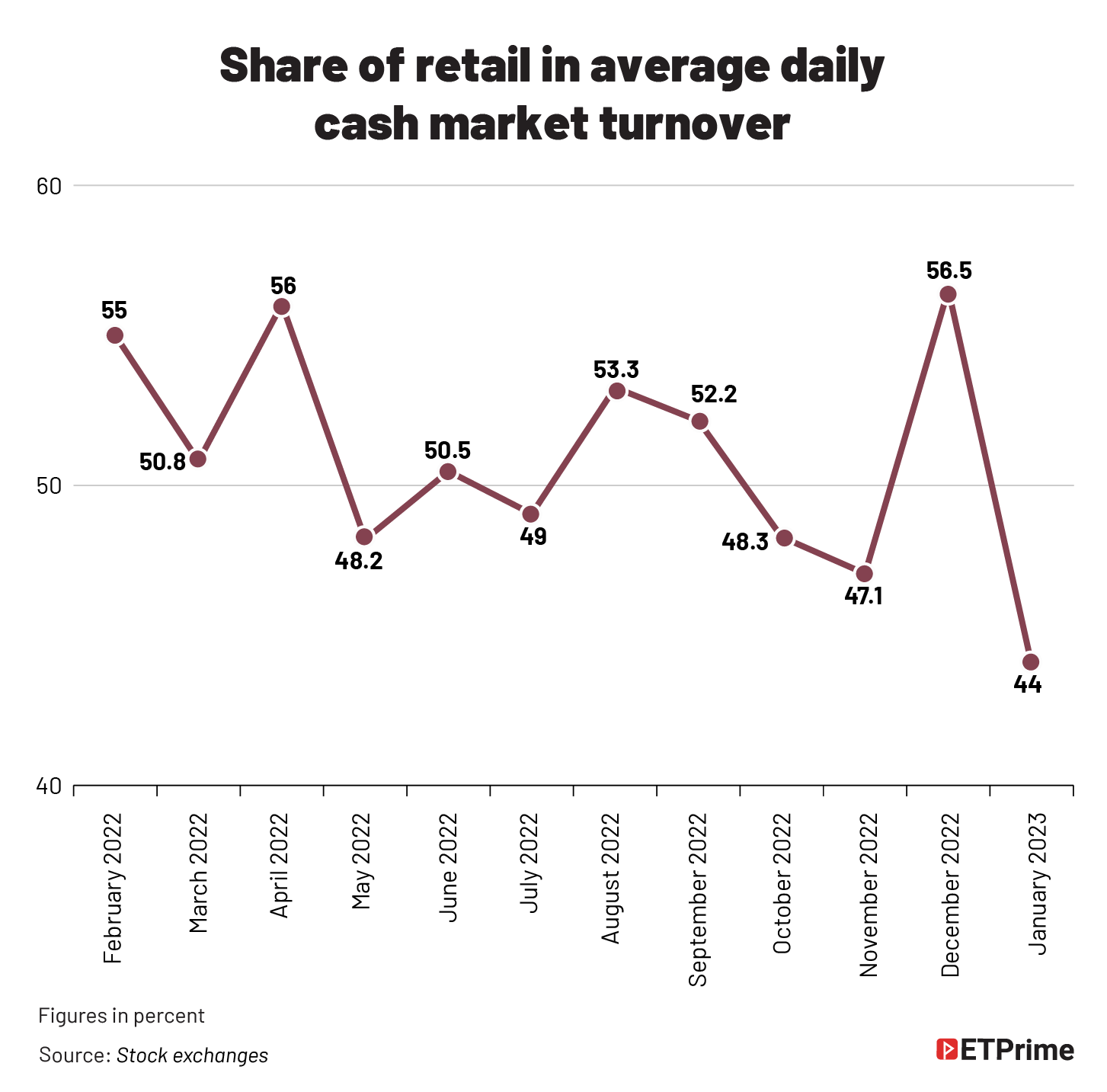

Consider this: Between March 2020 (when the lockdown was imposed in India) and January 2023, the share of retail investors in the cash market fell to 44% from 66%. But at the same time, retail fund flows into systematic investment plans (SIP) remain vibrant.

So, what is fuelling this?

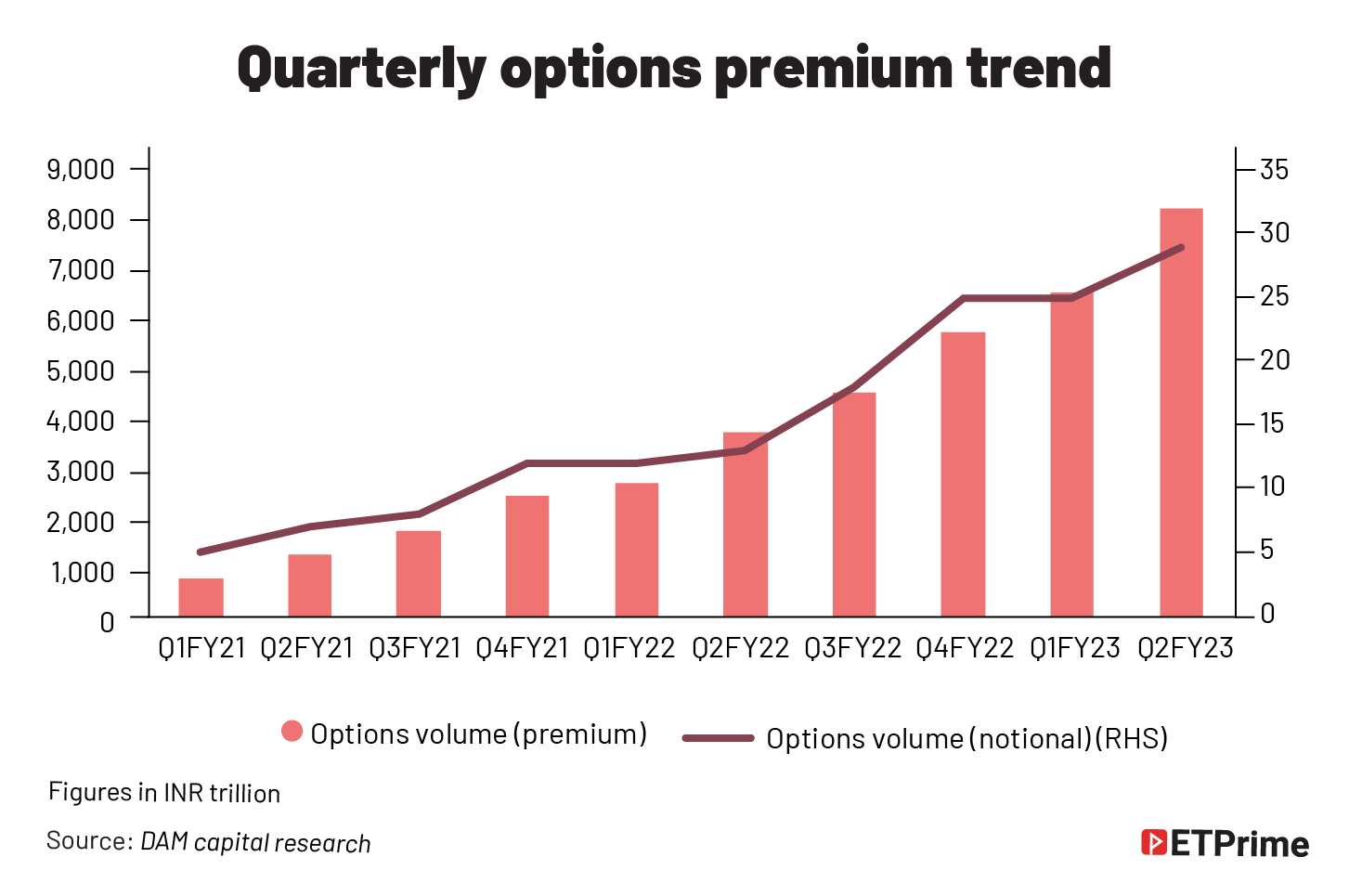

Clearly, retail investors are now willing to take more risks in the esoteric world of derivatives market. This behavioural change is the result of a quest for dopamine rush in the age of social media and instant gratification.

The big question is: Will it end well?

A vicious cycle

The long-term outcome of bets in the derivatives segment is determined by the skill level, knowledge, experience, and temperament of the individual trader. But traders with the right mix of these inevitable qualities are a rarity, especially in the retailer segment.

In January this year, the market regulator Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) released a report on the futures and options (F&O) market in the country. It revealed that 89% of individual traders in the equity F&O segment incurred an average loss of INR1.1 lakh during FY22.

These numbers tell us of how overconfident human beings are when it comes to trading in stock markets and how difficult it is to make money in derivatives. Most retail traders are not even aware of the magnitude of risk they take while dealing in this segment. Worse, there is a tendency among losing traders to take higher risks, a vicious cycle that only accelerates the destruction of a trading account.

To begin with, retail participants should understand that professional money managers with similar or higher skill sets can potentially make superlative returns by taking higher risks. But they are restricted by size. The bigger the fund, the lower the room for risk. In fact, smart fund managers are more diversified and take less risk.

In contrast, risk-taking is the norm among retail participants rather than the exception.

But is that the only reason?

Had it indeed been, all mutual fund schemes should have beaten their benchmark indices year after year since inception. That hasn’t happened.

If sophisticated investment vehicles with stringent risk management policies led by experienced and skilled professionals are finding it difficult to consistently beat Mr Market, it means there’s more to this puzzle than what meets the eye.

But before we try to solve it, here’s a small disclaimer. I tied myself to a post while writing this article, by the end of which you will know why.

The other side

In the 1990s, Renaissance Technologies’ Medallion fund was emerging as a big winner in most of its trades. While its founder and famous mathematician Jim Simons was happy, a thought kept on popping up in his head.

“Who is on the other side?” he often wondered.

Over time, “the man who solved the market” concluded that Renaissance was exploiting behavioural biases of other professional traders, both big and small.

“The manager of a global hedge fund, who is guessing on a frequent basis the direction of the French bond market, may be a more exploitable participant,” Simons had said.

His partner, Henry Laufer, had a different take. He believed that it was a different set of traders known for both their excessive trading and overconfidence. According to Laufer, “It’s a lot of dentists” or retail investors.

Most academicians and ‘passive’ investment management firms are of the view that stock markets are “always efficient”, suggesting that there is no way to consistently beat the market and that investors are rational.

But this has been proven incorrect. While markets are “generally” efficient and quite hard to beat, there is a big difference between the terms “always” and “generally”.

In 2013, the Nobel Prize in Economics was shared by Eugene Fama and Robert Shiller who have completely divergent views on the efficiency of markets. Further, the view that investors are rational is more problematic, because as per behavioural economics, which has a fair amount of literature and empirical evidence, most investors (not just retail) have cognitive biases.

Such biases lead to anomalies in investor behaviour. Among the most common ones are:

#1. Loss aversion: Investors generally feel the pain from negative events twice as much as the pleasure from positive ones.

#2. Anchoring: How judgment is skewed by an initial piece of information or experience.

#3. Endowment effect: How investors assign excessive value to what they already own in their portfolios.

Therefore, like Fama and Shiller, Simons and Laufer could also be right about who is on the other side of the trade despite their diverging views. But Laufer’s “dentists” seem to be shrinking in numbers when it comes to directly investing in equities and seem to be drawn to derivatives.

From FDs to equities

Investor behaviour in India has undergone a huge shift over the last 15 years and this was more pronounced since the demonetisation of high-value currencies in November 2016. As per an RBI memo dated August 2017, a major positive impact of demonetisation has been a shift to formal channels of saving by households. Moreover, there was an increase in flow of household savings into equity/debt-oriented mutual funds and life insurance policies.

In terms of assets under custody, the total equity holdings of domestic investment industry at INR135 lakh crore is more than twice that of foreign portfolio investors (FPI) holding of INR51 lakh crore, as per the category-wise data for all clients available on the National Securities Depository Ltd (NSDL).

While Indians have traditionally invested in fixed income instruments such as bank fixed deposits (FDs) which accounted for 41% of the household savings pie as of March 2022, this is gradually changing with the increasing adoption of capital market products. Within the investment landscape, the share of equity has increased from 24% in fiscal 2017 to 31% in fiscal 2022.

SIP’in up shares

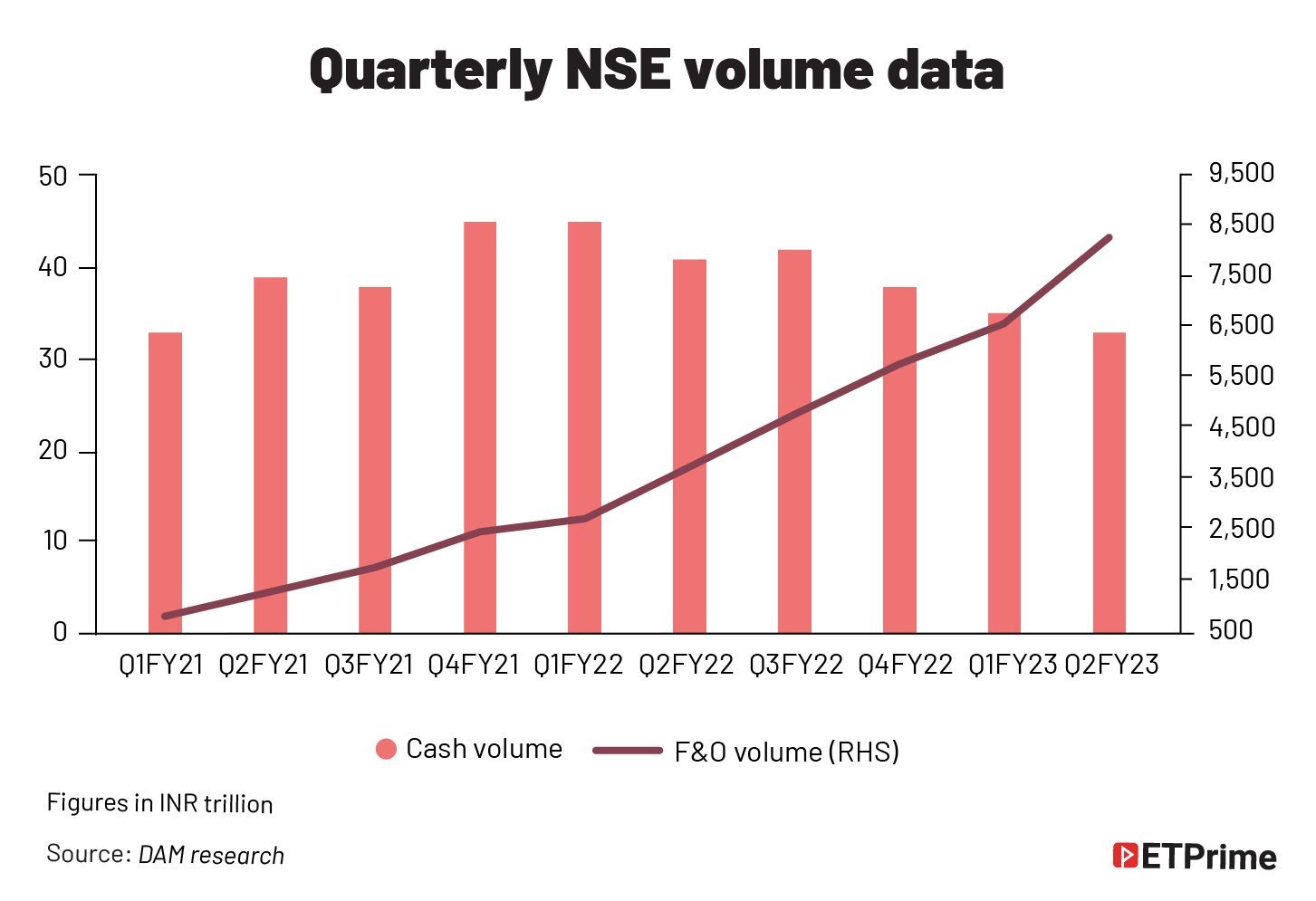

Another highlight of the shifting trend in investor preferences is that direct investing seems to have lost lustre. For instance, participation of retail investors in the cash market dropped to a 34-month low in January 2023 amid choppy market conditions and the revival of fixed-income assets in the wake of rising interest rates. Average daily cash-market volumes of non-institutional investors, mainly retail and high net-worth individuals, were at INR22,829 crore in January 2023, the lowest since March 2020 and 61% below the peak of INR58,409 crore recorded in February 2021, according to exchange data.

The share of retail investors, too, has fallen to 44% from 66% in daily cash market volumes. The number of active accounts on the NSE was at 3.4 crore in January, down 10% from June 2022.

However, SIP inflows continue to show steady growth. In fact, investments under systematic plans in the last three years have acted as a major support against selling by FPIs.

Paradox of skill

If retail investors are increasingly withdrawing from the cash segment, then the balance would tilt more in favour of Simons’ theory that on the other side of his winning bets when it comes to investing will other fund managers. This is what Michael Mauboussin, Head of consilient research at Counterpoint Global, calls ‘paradox of skill’ — a phenomenon in which shorter-term outcomes become more random or prone to luck as the skill levels of the talent pool continues to rise.

When paradox of skill kicks in, a systems-driven approach to investing and trading is more effective than a discretionary one so as to achieve a skill-based edge over the longer run.

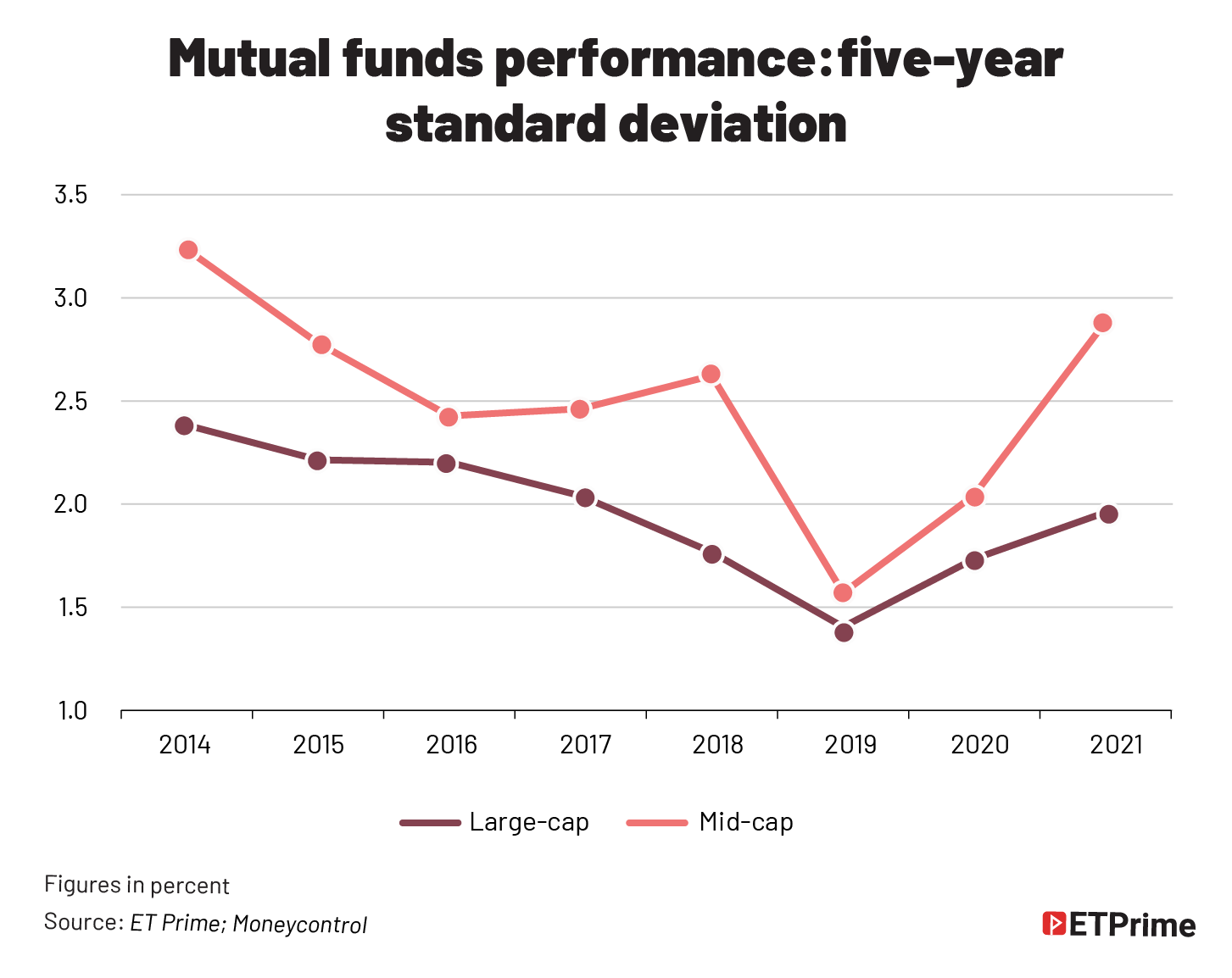

In the mutual fund industry today, the standard deviation of 10, five, and three-year returns has dropped dramatically. In simple terms, it means the gap in returns between the top five funds and the next five has shrunk.

The performance of funds is also prone to mean reversion. This means while it is certain that some large, mid- or small-cap fund manager will outperform peers, it is impossible pick that winner will as top performers keep changing.

The above two graphs bring to my mind two terms: closet indexing and career risk. In 2020, there was a reset in standard deviations as markets became volatile. On a yearly- or three-yearly basis, funds gave varied returns and standard deviations were high. But when we look at their performance over the long term, say five to 10 years, the larger trend continues. Fund management is a tough business and the gaps in returns are narrowing.

Paradox of Skill is evident in sports, too. Data from the English Football League shows that the number of matches ending in a draw has more than doubled over a century despite rules being changed to keep the sport more competitive and exciting. This is because the overall skill levels have risen with the improvement in coaching facilities, amenities, support staff, analytics, and so on.

So, can we develop an edge when paradox of skill is constantly at play?

The pillars of investing

Former Indian cricket captain MS Dhoni once said in what’s now considered an iconic interview, “I often talk about how the process is more important than the result… the result is just a by-product… But in today’s world, we are so focused on the by-product that we get away from the process. So, take care of the process, all the small things, and eventually you will get the desired result”.

Captain Cool’s on-field success formula is also one of the major pillars of investing.

Analysis, process, and behavior form the three-pronged approach to successful investing. Analytical edge gained from superior fundamental analysis and access to data and information can often question the conclusion that the performance gap between the best- and worst-performing funds is narrowing. This means that to succeed in the market, retail investors, too, will have to develop a process-driven edge and work on behaviourial vulnerabilities due to human emotions. This is where an empirical and evidence based approach comes in.

Data don’t lie

In his book Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game, Michael Lewis covers the aspect of analytical and process-driven statistical edge and instinct-based decision making through the lens of Oakland Athletics baseball team’s general manager, Billy Beane. Later made into a movie titled Moneyball, it takes us through Beane’s (played by Brad Pitt) efforts to build a baseball team on a tight budget by relying on computer-driven data analysis to pick the best players.

In the movie, in contrast to Beane’s approach there is a committee of old-school scouts trying to pick players largely based on their own instincts. There is a scene in it which resembles pitting 20 fundamental discretionary stock pickers against a single investor who follows quantitative analysis.

It goes like this:

Beane tries to explain a data-driven approach to player selection. He holds a meeting with the old-school scouts where they discuss how to replace three of the team’s best players lost to rivals. The old-school scouts discuss and offer evaluations that are subjective, based on impressions rather than objective and empirical evidences.

“I like Perez. He swings like a man,” says one.

“I like the way he walks into a room,” opines another.

“He’s ready to play the part. He just needs some playing time,” shouts a third one.

At this point, Beane, explains his new data-driven approach based purely on statistics and ignores extraneous factors such as the player’s swag or popularity. Predictably, he faces huge resistance from the scouts.

“You don’t put a team together for the computer, Billy. Baseball isn’t just numbers. It’s not science… They don’t have our experience and they don’t have our intuition… There are intangibles… You’re discounting what scouts have done 150 years,” they tell him.

“Adapt or die,” Beane shoots back.

Of course, Beane is not suggesting that one should blindly let computers make all the decisions. All he is saying is that one should take data into account and see how fits into the scheme of larger things — just like how various parameters such as valuations, momentum, quality, and volatility are used to build a portfolio of top-ranked stocks.

The above approach is in contrast to a discretionary fund manager’s process wherein she may pick stocks purely based on individual discretion before deriving factor attributes from the overall portfolio holdings.

To be sure, even discretionary investors and fund managers have some systems and processes though it may not be possible to codify them as opposed a quantitative systematic approach. A quant-fund manager, too, may exercise discretion while executing if the situation demands.

Surgeon and author Atul Gawande’s book, The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, is a great read on how checks and balances help in eliminating errors. When humans are involved in a process, there can be small lapses which can prove fatal, especially when the steps become repetitive leading to heuristics or short cut-driven decision-making process. However, having a checklist like the one below helps in reducing such mis-steps:

#1. Identify blind spots

#2. Increase consistency

#3. Reduce bias

#4. Improve continuously

When paradox of skill starts its work and analytical edge starts eroding in investing, a behavioural- and process-driven approach will separate outperformers and underperformers. Hence, having a process or system to drive investment decisions and following that confidently even during tough times is what gives an investor the real edge in markets.

Being human

Jeff Bezos once asked Buffett, “Your investment thesis is so simple… you’re the second richest guy in the world, and it’s so simple. Why doesn’t everyone just copy you?”

And the Oracle of Omaha replied, “Because nobody wants to get rich slow”.

Patience is key in the long-term game of investing and a solid set of data-driven systems and processes would go a long way. But how much of it should be left to the computer?

Let’s try to answer that with a few counter-questions. Have aircraft pilots been replaced by machines? Do quant-fund managers hand over the entire investment process to computers? Do authors use their creativity while writing a book using chatGPT?

We all know the answers. Humans are the key to any logically driven decision-making process. However, the execution part, albeit with enough oversight, is handed over to machines.

Machines give human beings an edge to overcome many errors. Our brains are over 150,000 years old. But the markets are only 400 years old and we are using our hunter-gatherer like brains in the stock market, which is designed for rational minds. We see danger when there is none and we panic when we should be calm to take advantage of the situation.

From Tulip mania to South Sea Bubble to Great Depression to Black Monday (1987) to Asian currency crisis to dot-com bubble to the 2008 financial crisis and more recently the Covid-19 crash, each major event in the history of stock market has proved one thing — the trigger event may vary but human behaviour doesn’t. Salman Khan would simply call it “Being human”.

Sticking to the strategy

Greek king Odysseus was probably the original forefather of systematic investors. Warned by goddess Circe that on the way back to Ithaca he would encounter the Sirens, or winged monster women who lure sailors with their melodious singing and cause ship wrecks, Odysseus devised a plan.

He asked his crew to tie him to a post and ordered them to close their ears with beeswax. Irrespective of how much he begged and pleaded, under no condition were they to untie him.

Cliff Asness, co-founder of AQR Capital Management, had said in an interview in 2019, “A huge part of our job is building a great investment process that will make money over the long term, but a fair amount of our job is sticking to it like ‘grim death’ during the tougher times”.

So, what do Odysseus and Asness have in common?

They both know they must tie themselves up to a post (just like how this author did before starting to write this article). However tempting and seductive the singing of the market’s Sirens becomes, fund managers like Asness won’t override their investment process. Because they know that to survive this journey, they should remain tied to the proverbial post.

Speaking to The Economist recently about the comeback of value investing, Asness shared his experience during the valuation bubble of 1999-2000 and added that 2018-20 was very similar. During that period, AQR conducted an analysis excluding tech stocks and found similar results to that in 1999-2000. The conclusion was that the investment world seemed to be a bit crazy and hence the most sensible thing to do was to stick with the strategy.

The bottom line

While value investing (buying cheap companies and shorting expensive ones) has done well recently in 2021-22, the valuation spread between the two is still close to the dot-com bubble and Covid-19 peak. When it is close to ‘maximum crazy’, one good year usually doesn’t fix it as investors tend to think that the correction is over.

When asked whether he ever thought of throwing in the towel, Asness admitted that at times he faced a ‘crisis of confidence’ in the middle of the night and doubted whether he has plain lucky over the last 25 years or whether the encouraging results in the past were because of data-mining, analysis, and a systematic approach to investing.

Asness thinks it’s normal to have such self doubts once in a while and that anyone who doesn’t have them is either dishonest or crazy. However, he says if one understands her individual investment style may underperform during tough times while long-term evidence shows its performance is strong, it should give enough confidence to stick to the strategy like “grim death”.

But that’s not easy. That’s why a data-driven edge — even there are unknowns — is not a fleeting phenomenon but rather a long-term edge.

Disclaimer: Nothing in this article should be construed as investment advice. This is purely for educational purposes only. Please consult an investment advisor before investing

(Originally published on Mar 6, 2023)